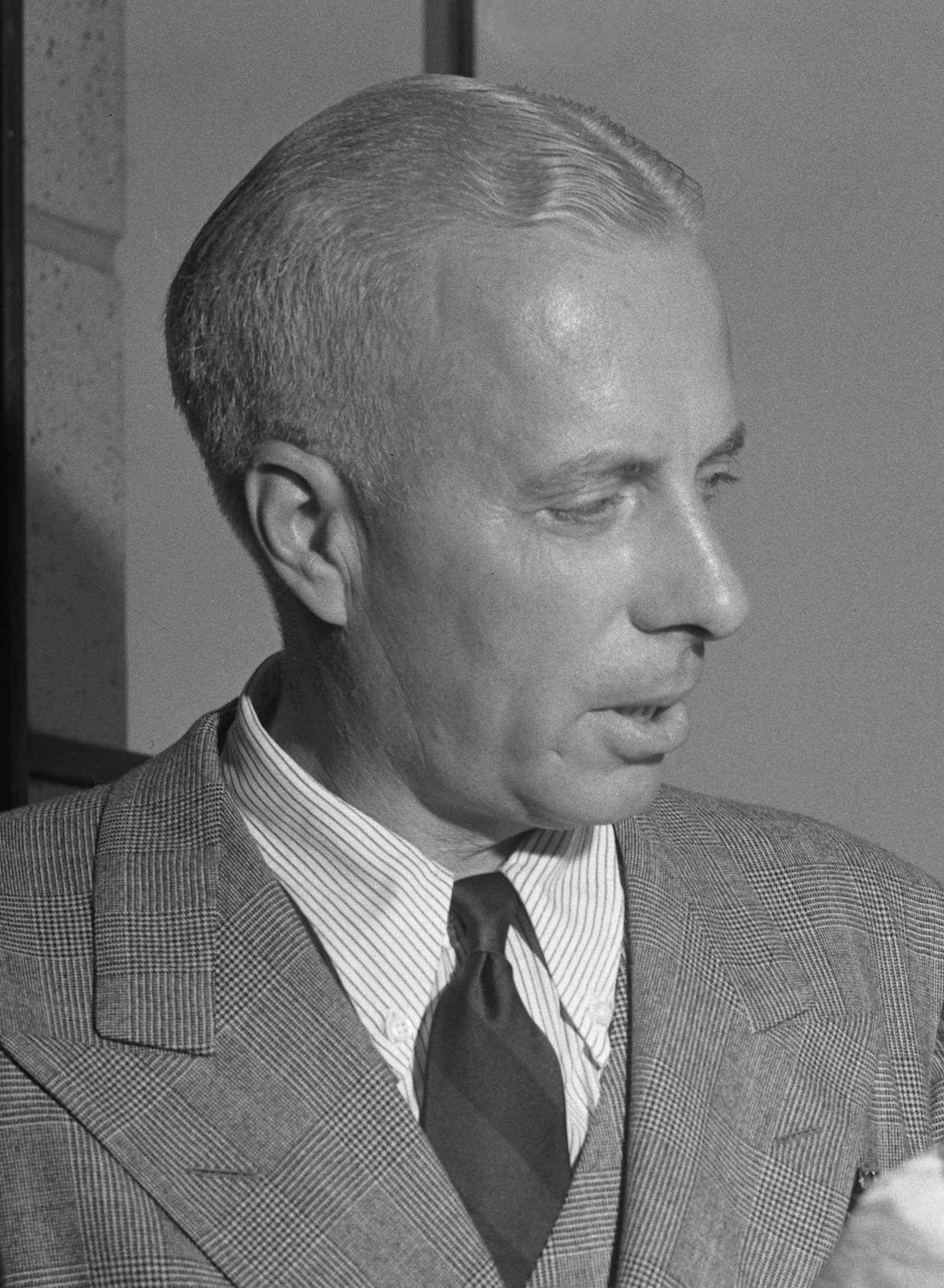

Howard Hawks Peter John Ward Hawks

| Bringing Up Baby | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release affiche | |

| Directed by | Howard Hawks |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Hagar Wilde |

| Based on | Bringing Up Baby 1937 brusque story in Collier'southward past Hagar Wilde |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Russell Metty |

| Edited by | George Hively |

| Music by |

|

| Product | RKO Radio Pictures |

| Distributed past | RKO Radio Pictures |

| Release date |

|

| Running time | 102 minutes |

| Land | Usa |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $i.1 million |

| Box function | $ane.1 one thousand thousand |

Bringing Upwardly Baby is a 1938 American screwball comedy motion picture directed by Howard Hawks, and starring Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant. It was released past RKO Radio Pictures. The film tells the story of a paleontologist in a number of predicaments involving a bird-brained heiress and a leopard named Baby. The screenplay was adapted past Dudley Nichols and Hagar Wilde from a curt story by Wilde which originally appeared in Collier'southward Weekly magazine on Apr 10, 1937.

The script was written specifically for Hepburn, and tailored to her personality. Filming began in September 1937 and wrapped in January 1938, over schedule and over budget. Product was frequently delayed past uncontrollable laughing fits between Hepburn and Grant. Hepburn struggled with her comedic operation and was coached by another bandage member, vaudeville veteran Walter Catlett. A tame leopard was used during the shooting; its trainer stood off-screen with a whip for all of its scenes.

Bringing Up Babe was a commercial flop at release, although information technology eventually fabricated a pocket-size profit later on its re-release in the early on 1940s. Shortly after the moving picture'south premiere, Hepburn was one of a group of actors labeled as "box role poisonous substance" by the Independent Theatre Owners of America. Her career would not recover until The Philadelphia Story two years after. The film's reputation began to grow during the 1950s when it was shown on television.

Since and so, the picture show has gained acclamation from both critics and audiences for its zany antics and pratfalls, absurd situations and misunderstandings, perfect sense of comic timing, completely screwball cast, series of lunatic and hare-brained misadventures, disasters, light-hearted surprises and romantic comedy.[2]

In 1990, Bringing Up Baby was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress every bit "culturally, historically, or aesthetically pregnant,"[3] [4] and it has appeared on a number of greatest-films lists, ranking 88th on the American Film Institute'due south 100 greatest American films of all time list.

Plot [edit]

David Huxley (Cary Grant) is a mild-mannered paleontologist. For the past four years, he has been trying to assemble the skeleton of a Brontosaurus merely is missing one bone: the "intercostal clavicle." Calculation to his stress is his impending marriage to the dour Alice Swallow (Virginia Walker) and the demand to impress Elizabeth Random (May Robson), who is considering a million-dollar donation to his museum.

The day before his wedding, David meets Susan Vance (Katharine Hepburn) past take chances on a golf form when she plays his ball. She is a gratuitous-spirited, somewhat scatterbrained, young lady, unfettered by logic. These qualities soon embroil David in several frustrating incidents.

Susan's brother Mark has sent her a tame leopard named Babe (Nissa) from Brazil. Its tameness is helped by hearing the song "I Can't Give You lot Anything But Beloved". Susan thinks David is a zoologist, and manipulates him into accompanying her in taking Baby to her farm in Connecticut. Complications arise when Susan falls in beloved with him, and she tries to continue him at her business firm every bit long as possible, fifty-fifty hiding his clothes, to forbid his imminent wedlock.

David'southward prized intercostal clavicle is delivered, but Susan'southward aunt's dog George (Skippy) takes information technology and buries information technology somewhere. When Susan's aunt arrives, she discovers David in a negligee. To David'southward dismay, she turns out to be potential donor Elizabeth Random. A second message from Mark makes articulate the leopard is for Elizabeth, as she always wanted one. Baby and George run off. The zoo is called to help capture Baby. Susan and David race to find Infant before the zoo and, mistaking a unsafe leopard (likewise portrayed by Nissa) from a nearby circus for Babe, they let it out of its cage.

David and Susan are jailed by a befuddled town policeman, Constable Slocum (Walter Catlett), for acting strangely at the house of Dr. Fritz Lehman (Fritz Feld), where they had cornered the circus leopard, thinking it was Baby. When Slocum does not believe their story, Susan tells him they are members of the "Leopard Gang"; she calls herself "Swingin' Door Susie," and David "Jerry the Nipper."[a] Somewhen, Alexander Peabody (George Irving) shows upwards to verify everyone's identity. Susan, who escaped out of a window during a police interview, unwittingly drags the highly irritated circus leopard into the jail. David saves her, using a chair to shoo the big cat into a cell.

Some time later, Susan finds David, who has been jilted by Alice because of her, on a high platform working on his brontosaurus reconstruction at the museum. Subsequently showing him the missing bone which she plant by abaft George for three days, Susan, against his warnings, climbs a tall ladder side by side to the dinosaur to be closer to him. She tells David that her aunt has given her the 1000000 dollars, and she wants to donate information technology to the museum, merely David is more interested in telling her that the 24-hour interval spent with her was the best day of his life. They profess their love for each other as Susan unconsciously swings the ladder from side to side, and as information technology sways more than and more with each swing Susan and David finally detect the ladder moving and that Susan is in danger. Frightened, she climbs onto the skeleton, causing information technology to plummet, and David grabs her paw only as she falls. Afterwards she dangles for a few seconds, David lifts her onto the platform. After she talks him into forgiving her without him saying a give-and-take about anything but halfheartedly complaining about the loss of his years of piece of work putting together the Brontosaurus skeleton, David, resigning himself to a future of chaos, embraces Susan.

Bandage [edit]

| Uncredited

Animals

|

Production [edit]

Evolution and writing [edit]

In March 1937, Howard Hawks signed a contract at RKO for an accommodation of Rudyard Kipling's Gunga Din, which had been in pre-product since the previous fall. When RKO was unable to infringe Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and Franchot Tone from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for the film and the adaptation of Gunga Din was delayed, Hawks began looking for a new project. In Apr 1937, he read a brusque story by Hagar Wilde in Collier'due south magazine called "Bringing Up Baby" and immediately wanted to brand a flick from information technology,[five] remembering that it made him laugh out loud.[6] RKO bought the screen rights in June[vii] for $1,004, and Hawks worked briefly with Wilde on the motion picture'south handling.[viii] Wilde's short story differed significantly from the moving-picture show: David and Susan are engaged, he is not a scientist and there is no dinosaur, intercostal clavicle or museum. However, Susan gets a pet panther from her brother Mark to give to their Aunt Elizabeth; David and Susan must capture the panther in the Connecticut wilderness with the assistance of Infant's favorite vocal, "I Can't Requite You Anything merely Dear, Baby".[vii]

Hawks and then hired screenwriter Dudley Nichols, all-time known for his work with manager John Ford, for the script. Wilde would develop the characters and comedic elements of the script, while Nichols would take care of the story and structure. Hawks worked with the two writers during summer 1937, and they came up with a 202-page script.[9] Wilde and Nichols wrote several drafts together, beginning a romantic relationship and co-authoring the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers film Carefree a few months later.[7] The Bringing Up Baby script underwent several changes, and at one bespeak there was an elaborate pie fight, inspired by Mack Sennett films. Major Applegate had an assistant and food taster named Ali (which was intended to exist played by Mischa Auer), but this grapheme was replaced with Aloysius Gogarty. The script'southward final draft had several scenes in the eye of the motion-picture show in which David and Susan declare their love for each other which Hawks cut during production.[10]

Nichols was instructed to write the moving-picture show for Hepburn, with whom he had worked on John Ford'due south Mary of Scotland (1936).[11] Barbara Leaming alleged that Ford had an thing with Hepburn, and claims that many of the characteristics of Susan and David were based on Hepburn and Ford.[12] Nichols was in touch with Ford during the screenwriting, and the film included such members of the John Ford Stock Visitor every bit Ward Bond, Barry Fitzgerald, D'Arcy Corrigan and associate producer Cliff Reid.[13] John Ford was a friend of Hawks, and visited the set up. The round spectacles Grant wears in the flick are reminiscent of Harold Lloyd and of Ford.[14]

Filming was scheduled to begin on September one, 1937 and wrap on October 31, but was delayed for several reasons. Product had to wait until mid-September to clear the rights for "I Can't Requite You Anything just Love, Infant" for $1,000. In August, Hawks hired gag writers Robert McGowan and Gertrude Purcell[15] for uncredited script rewrites, and McGowan added a scene inspired by the comic strip Professor Dinglehoofer and his Canis familiaris in which a dog buries a rare dinosaur os.[10] RKO paid King Features $one,000 to apply the idea for the film on September 21.[xvi]

Unscripted ad-lib past Grant [edit]

It has been debated whether Bringing Upward Infant is the first fictional work (apart from pornography) to use the discussion gay in a homosexual context.[17] [xviii] In ane scene, Cary Grant's character is wearing a woman's marabou-trimmed négligée; when asked why, he replies exasperatedly "Because I just went gay of a sudden!" (leaping into the air at the discussion gay). As the term gay was not familiar to the general public until the Stonewall riots in 1969,[xix] it is questioned whether the word is used by Grant in its original sense (meaning "happy")[xx] or is an intentional, joking reference to homosexuality.[20]

The line in the picture show was an ad-lib by Grant, and was not in the script.[21] According to Vito Russo in The Celluloid Cupboard (1981, revised 1987), the script originally had Grant's character say "I...I suppose you think it'southward odd, my wearing this. I realize it looks odd...I don't unremarkably...I mean, I don't own one of these". Russo suggests that this indicates that people in Hollywood (at least in Grant's circles) were familiar with the slang connotations of the word; however, neither Grant nor anyone involved in the film suggested this.[19]

The 1933 film My Weakness had previously used the word "gay" as an overt descriptor of homosexuality; one of two men pining away for the same adult female all of a sudden suggests a solution to their mutual trouble: "Let's be gay!" However, the Studio Relations Commission censors decreed that the line was as well risqué and had to exist muffled.[22] The film This Side of Sky (1934) included a scene in which a fussy, gossipy interior decorator tries to sell a floral fabric pattern to a customer, who knowingly replies, "It strikes me as a scrap likewise gay."[23]

Casting [edit]

Hepburn and Grant in their 2nd of four picture collaborations

After briefly considering Hawks' cousin Carole Lombard for the office of Susan Vance, producers chose Katharine Hepburn to play the wealthy New Englander considering of her background and similarities to the graphic symbol. RKO agreed to the casting, but had reservations considering of Hepburn'southward salary and lack of box-office success for several years.[9] Producer Lou Lusty said, "You couldn't even interruption fifty-fifty, if a Hepburn show price eight hundred grand."[16] At offset, Hawks and producer Pandro S. Berman could non agree on whom to cast in the function of David Huxley. Hawks initially wanted silent-pic comedian Harold Lloyd; Berman rejected Lloyd and Ronald Colman, offering the office to Robert Montgomery, Fredric March and Ray Milland (all of whom turned it down).[24]

Hawks' friend Howard Hughes finally suggested Cary Grant for the role.[25] Grant had just finished shooting his breakthrough romantic one-act The Awful Truth (1937),[nine] and Hawks may have seen a rough cut of the unreleased film.[16] Grant so had a non-exclusive, 4-picture deal with RKO for $l,000 per moving picture, and Grant's director used his casting in the film to renegotiate his contract, earning him $75,000 plus the bonuses Hepburn was receiving.[24] Grant was concerned about beingness able to play an intellectual character and took 2 weeks to accept the function, despite the new contract. Hawks built Grant'due south conviction past promising to coach him throughout the movie, instructing him to watch Harold Lloyd films for inspiration.[26] Grant met with Howard Hughes throughout the film to talk over his character, which he said helped his performance.[26]

Hawks obtained character actors Charlie Ruggles on loan from Paramount Pictures for Major Horace Applegate and Barry Fitzgerald on loan from The Mary Pickford Corporation to play gardener Aloysius Gogarty.[9] Hawks bandage Virginia Walker as Alice Eat, David'southward fiancée; Walker was nether contract to him and later married his brother William Hawks.[27] Equally Hawks could not find a panther that would work for the film, Infant was changed to a leopard so they could bandage the trained leopard Nissa, who had worked in films for eight years, making several B-movies.[16]

Filming [edit]

Shooting began September 23, 1937, and was scheduled to end November 20, 1937,[28] on a budget of $767,676.[29] Filming began in-studio with the scenes in Susan's apartment, moving to the Bel Air Country Society in early October for the golf game-class scenes.[16] The product had a hard start due to Hepburn's struggles with her graphic symbol and her comedic abilities. She frequently overacted, trying too difficult to be funny,[29] and Hawks asked vaudeville veteran Walter Catlett to assist coach her. Catlett acted out scenes with Grant for Hepburn, showing her that he was funnier when he was serious. Hepburn understood, acted naturally and played herself for the rest of the shoot; she was then impressed by Catlett's talent and coaching ability that she insisted he play Constable Slocum in the film.[thirty] [31]

Katharine Hepburn and Nissa in a publicity photo; at one betoken, Nissa lunged at Hepburn and was only stopped by the trainer's whip.

Nearly shooting was done at the Arthur Ranch in the San Fernando Valley, which was used as Aunt Elizabeth'south manor for interior and outside scenes.[xvi] Get-go at the Arthur Ranch shoot,[21] Grant and Hepburn often ad-libbed their dialogue and often delayed production by making each other laugh.[32] The scene where Grant frantically asks Hepburn where his bone is was shot from 10 am until well after iv pm considering of the stars' laughing fits.[33] After one month of shooting Hawks was seven days behind schedule. During the filming, Hawks would refer to four unlike versions of the film's script and brand frequent changes to scenes and dialogue.[21] His leisurely attitude on prepare and shutting down production to come across a equus caballus race contributed to the lost fourth dimension.[33] He took twelve days to shoot the Westlake jail scene instead of the scheduled v.[21] Hawks after facetiously blamed the setbacks on his two stars' laughing fits and having to piece of work with ii animal actors.[33]

The terrier George was played by Skippy, known as Asta in The Thin Man picture show series and co-starring with Grant (every bit Mr. Smith) in The Awful Truth. The tame leopard Babe and the escaped circus leopard were both played by a trained leopard, Nissa. The big cat was supervised by its trainer, Olga Celeste, who stood past with a whip during shooting. At i point, when Hepburn spun around (causing her skirt to twirl) Nissa lunged at her and was subdued when Celeste croaky her whip. Hepburn wore heavy perfume to continue Nissa at-home and was unafraid of the leopard, but Grant was terrified; almost scenes of the two interacting are done in close-up with a stand up-in. Hepburn played upon his fear past throwing a toy leopard through the roof of Grant's dressing room during production.[33] There were several news reports almost Hawks' difficulty filming the live leopard, and the potential danger to highly valuable actors, so some scenes required rear-screen projection,[34] while several others were shot using traveling mattes. In a scene where Grant has Infant on a leash, it is quite obvious that the leash was hand painted on motion picture because it proved impossible to make the two parts of the leash join in the traveling matte.

Hawks and Hepburn had a confrontation ane day during shooting. While Hepburn was chatting with a coiffure member, Hawks yelled "Quiet!" until the merely person however talking was Hepburn. When Hepburn paused and realized that anybody was looking at her, she asked what was the matter. Hawks asked her if she was finished imitating a parrot. Hepburn took Hawks bated, telling him never to talk to her like that again since she was old friends with virtually of the crew. When Hawks (an even older friend of the crew) asked a lighting tech whom he would rather drop a light on, Hepburn agreed to behave on fix. A variation of this scene, with Grant yelling "Quiet!", was incorporated into the motion picture.[31] [35]

The Westlake Street ready was shot at 20th Century Fox Studios.[15] Filming was somewhen completed on Jan 6, 1938 with the scenes outside Mr. Peabody's firm. RKO producers expressed business organization virtually the picture'due south delays and expense, coming in twoscore days over schedule and $330,000 over budget, and also disliked Grant'due south glasses and Hepburn's hair.[35] The moving-picture show's final toll was $i,096,796.23, primarily due to overtime clauses in Hawks', Grant's and Hepburn'due south contracts.[28] The picture's cost for sets and props was only $5,000 over budget, but all actors (including Nissa and Skippy) were paid approximately double their initial salaries. Hepburn'southward salary rose from $72,500 to $121,680.50, Grant'due south salary from $75,000 to $123,437.50 and Hawks' bacon from $88,046.25 to $202,500. The director received an boosted $40,000 to finish his RKO contract on March 21, 1938.[36]

Mail service-production and previews [edit]

Hawks' editor, George Hively, cutting the film during production and the final prints were made a few days subsequently shooting concluded.[28] The first cut of the motion picture (x,150 anxiety long)[37] was sent to the Hayes Office in mid-January.[38] Despite several double entendres and sexual references it passed the picture,[28] overlooking Grant saying he "went gay" or Hepburn'southward reference to George urinating. The censor'south simply objections were to the scene where Hepburn's clothes is torn, and references to politicians (such as Al Smith and Jim Farley).[38]

Similar all Hawks' comedies, the flick is fast paced (despite beingness filmed primarily in long medium shots, with little cantankerous-cutting). Hawks told Peter Bogdanovich, "You get more pace if yous pace the actors quickly within the frame rather than cross cut fast".[34]

Past February 18, the pic had been cut to 9,204 feet.[38] It had two advance previews in January 1938, where information technology received either Equally or A-pluses on audience-feedback cards. Producer Pandro S. Berman wanted to cut five more minutes, but relented when Hawks, Grant and Cliff Reid objected.[38] At the moving-picture show'south second preview, the film received rave reviews and RKO expected a striking.[28] The film'due south musical score is minimal, primarily Grant and Hepburn singing "I Tin't Give You lot Anything But Honey, Baby". There is incidental music in the Ritz scene, and an arrangement of "I Can't Give You Anything Just Beloved, Babe" during the opening and closing credits by musical director Roy Webb.[39]

Reception [edit]

Disquisitional response [edit]

The flick was premiered on Feb 16, 1938 at the Golden Gate Theatre in San Francisco, before receiving a wide release on November 23, 1938.[ citation needed ] It received skilful accelerate reviews, with Otis Ferguson of The New Republic writing the movie was very funny, and praising Hawks' management.[twoscore] Diverseness as well praised the film, singling out Hawks' pacing and direction, calling Hepburn'south performance "one of her most invigorating screen characterizations" and maxim Grant "performs his role to the hilt";[41] their only criticism was the length of the jail scene.[42] Film Daily called it "literally a anarchism from starting time to finish, with the laugh total heavy and the action fast."[43] Harrison's Reports called the film "An excellent farce" with "many situations that provoke hearty laughter,"[44] and John Mosher of The New Yorker wrote that both stars "manage to exist funny" and that Hepburn had never "seemed then adept-natured."[45] However, Frank Southward. Nugent of The New York Times disliked the film, considering it derivative and cliché-ridden, a rehash of dozens of other screwball comedies of the period. He labeled Hepburn's performance "breathless, senseless, and terribly, terribly fatiguing",[46] and added, "If you've never been to the movies, Bringing Up Baby volition exist new to you – a zany-ridden production of the goofy-farce school. But who hasn't been to the movies?"[47]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 94% based on 46 reviews, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "With Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant at their effervescent all-time, Bringing Upwards Baby is a seamlessly assembled one-act with indelible appeal."[48] On Metacritic, the moving picture holds a weighted average score of 91 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[49]

Box part [edit]

Despite Bringing Up Baby 's reputation as a flop, it was successful in some parts of the U.Southward. The film premiered on February sixteen, 1938 at the Golden Gate Theatre in San Francisco (where it was a striking), and was also successful in Los Angeles, Portland, Denver, Cincinnati and Washington, D.C. However, it was a fiscal disappointment in the Midwest, as well as virtually other cities in the country, including NYC; to RKO's chagrin, the film'due south premiere in New York on March three, 1938 at Radio City Music Hall made merely $lxx,000 and it was pulled after i week[fifty] in favor of Jezebel with Bette Davis.[51]

During its first run, Bringing Up Baby made $715,000 in the U.S. and $394,000 in foreign markets for a total of $1,109,000;[36] its reissue in 1940 and 1941 made an additional $95,000 in the US and $55,000 in foreign markets.[50] Post-obit its second run, the film made a profit of $163,000.[36] Due to its perceived failure, Hawks was released early on from his two-film contract with RKO[36] and Gunga Din was somewhen directed by George Stevens.[52] Hawks later on said the film "had a great mistake and I learned an awful lot from that. In that location were no normal people in information technology. Everyone you met was a screwball and since that time I learned my lesson and don't intend e'er over again to make everybody crazy."[53] The manager went on to work with RKO on iii films over the next decade.[54] Long before Bringing Up Baby 's release, Hepburn had been branded "box office poison" by Harry Brandt (president of the Independent Theatre Owners of America) and thus was immune to purchase out her RKO contract for $22,000.[55] [56] However, many critics marveled at her new skill at low comedy; Life magazine called her "the surprise of the picture".[57] Hepburn'south former boyfriend Howard Hughes bought RKO in 1948, and sold information technology in 1955; when he sold the company, Hughes retained the copyright to six films (including Bringing Up Baby).[54]

Legacy [edit]

Bringing Upwardly Baby was the second of iv films starring Grant and Hepburn; the others were Sylvia Scarlett (1935), Holiday (1938) and The Philadelphia Story (1940). The movie'due south concept was described by philosopher Stanley Cavell as a "definitive achievement in the history of the art of film."[58] Cavell noted that Bringing Up Baby was made in a tradition of romantic comedy with inspiration from ancient Rome and Shakespeare.[59] Shakespeare's Much Ado Near Nothing and As You Similar It have been cited in particular as influences on the film and the screwball one-act in full general, with their "haughty, self-sufficient men, strong women and fierce combat of words and wit."[60] Hepburn'southward grapheme has been cited as an early example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl film archetype.[61]

The popularity of Bringing Up Baby has increased since it was shown on television receiver during the 1950s, and by the 1960s motion picture analysts (including the writers at Cahiers du Movie house in French republic) affirmed the picture show's quality. In a rebuttal of swain New York Times critic Nugent's scathing review of the film at the time of release, A. O. Scott has said that you'll "find yourself amazed at its freshness, its vigor, and its brilliance-qualities undiminished later sixty-5 years, and likely to withstand repeated viewings."[47] Leonard Maltin stated that information technology is now "considered the definitive screwball comedy, and 1 of the fastest, funniest films ever made; grand performances by all."[47]

Bringing Upward Baby has been adapted several times. Hawks recycled the nightclub scene in which Hepburn's apparel is torn and Grant walks behind her in the comedy Homo's Favorite Sport (1964). Peter Bogdanovich's film What's Up, Md? (1972), starring Barbra Streisand and Ryan O'Neal, was intended equally an homage to the film, and has contributed to its reputation.[53] In the commentary runway for Bringing Upwards Baby, Bogdanovich discusses how the coat-ripping scene in What's Up, Dr.? was based on the scene in which Grant's coat and Hepburn's dress are torn in Bringing Upwards Infant.[34]

The French film Une Femme ou Deux (English: One Adult female or Two; 1985), starring Gérard Depardieu, Sigourney Weaver, and Dr. Ruth Westheimer, is noted as a rework of Bringing Upwards Baby.[62] [63] [64] The movie Who'south That Girl? (1987), starring Madonna, is also loosely based on Bringing Upwards Baby.[65]

In 1990 (the registry's second yr), Bringing Upwardly Baby was selected for preservation in the National Flick Registry of the Library of Congress equally "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". Entertainment Weekly voted the film 24th on its listing of greatest films. In 2000, readers of Total Film magazine voted it the 47th-greatest comedy film of all time. Premiere ranked Cary Grant'south functioning every bit Dr. David Huxley 68th on its list of 100 all-fourth dimension greatest performances,[66] and ranked Susan Vance 21st on its list of 100 all-time greatest moving-picture show characters.[67]

The National Society of Movie Critics also included Bringing Up Baby in their "100 Essential Films", because it to be arguably the director'due south best picture show.[60]

The picture show is recognized by American Film Constitute in these lists:

- 1998: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #97[68]

- 2000: AFI'southward 100 Years...100 Laughs – #fourteen[69]

- 2002: AFI'southward 100 Years...100 Passions – #51[70]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- Dr. David Huxley: "It isn't that I don't similar you, Susan, because after all, in moments of quiet, I'm strangely fatigued toward you; but, well, there oasis't been any quiet moments!" – Nominated[71]

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #88[72]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Romantic One-act Film[73]

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Jerry the Nipper" was Irene Dunne's nickname for Grant's grapheme in The Awful Truth, which besides featured Asta

References [edit]

- ^ Hanson 1993, p. 235.

- ^ "Bringing Upwardly Baby (1938)". world wide web.filmsite.org . Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ^ Gamarekian, Barbara (Oct nineteen, 1990). "Library of Congress Adds 25 Titles to National Picture show Registry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress . Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 4.

- ^ Eliot 2004, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Mast 1988, p. 5.

- ^ McCarthy 1997, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d McCarthy 1997, p. 247.

- ^ a b Mast 1988, p. 6.

- ^ Leaming 1995, p. 348.

- ^ Leaming 1995, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Leaming 1995, pp. 348–9.

- ^ Leaming 1995, p. 349.

- ^ a b Mast 1988, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e f Mast 1988, p. 7.

- ^ "Censored Films and Boob tube at University of Virginia online". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Boswell 2009, p. 43.

- ^ a b Russo 1987, p. 47.

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas (2001–2013). "Gay". Online Etymology lexicon.

- ^ a b c d Mast 1988, p. 8.

- ^ Vieira, Mark A., Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Lawmaking Hollywood, Abrams, 1999, pg. 133

- ^ Vieira, Mark A., Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood, Abrams, 1999, pg. 168

- ^ a b Eliot 2004, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Eliot 2004, p. 174.

- ^ a b Eliot 2004, p. 178.

- ^ McCarthy 1997, p. 248.

- ^ a b c d east McCarthy 1997, p. 254.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1997, p. 250.

- ^ McCarthy 1997, pp. 250–251.

- ^ a b Mast 1988, p. 261.

- ^ McCarthy 1997, p. 251.

- ^ a b c d McCarthy 1997, p. 252.

- ^ a b c Bringing Up Baby DVD. Special Features. Peter Bogdanovich Sound Commentary. Turner Home Entertainment. 2005.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1997, p. 253.

- ^ a b c d Mast 1988, p. 14.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Mast 1988, p. 13.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 9.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 268.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 266.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 267.

- ^ "Reviews of the New Films". Film Daily: 12. February 11, 1938.

- ^ "Bringing Up Baby". Harrison's Reports: 31. February nineteen, 1938.

- ^ Mosher, John (March five, 1938). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 61–62.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 265.

- ^ a b c Laham 2009, p. 29.

- ^ "Bringing Up Infant (1938)". Rotten Tomatoes . Retrieved June iii, 2020.

- ^ "Bringing Upwards Babe reviews". Metacritic . Retrieved June iii, 2020.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1997, p. 255.

- ^ Brownish 1995, p. 140.

- ^ McCarthy 1997, p. 257.

- ^ a b McCarthy 1997, p. 256.

- ^ a b Mast 1988, p. 16.

- ^ Eliot 2004, pp. 180–i.

- ^ McCarthy 1997, pp. 255–7.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. xv.

- ^ Cavell 1981, p. 1.

- ^ Mast 1988, p. 3.

- ^ a b Carr 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Bowman, Donna; Gillette, Amelie; Hyden, Steven; Murray, Noel; Pierce, Leonard; Rabin, Nathan (August four, 2008). "Wild things: 16 films featuring Manic Pixie Dream Girls". The A.V. Club . Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ^ Steven H. Scheuer (1990). Movies on TV and Videocassette, 1991-1992

- ^ Martin Connors, Jim Craddock (1999). VideoHound'due south Aureate Movie Retriever 1999

- ^ Films and Filming, Issues 411-423, 1989.

- ^ "'Who's That Girl' (PG)". The Washington Post. Baronial 8, 1987. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ Premiere. "The 100 Greatest Characters of All Time". Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S., Apr 2004, retrieved November xviii, 2013.

- ^ Premiere. "The 100 Greatest Characters of All Fourth dimension". Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S., April 2006, retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI'southward 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI'due south 100 Years...100 Passions" (PDF). American Film Plant. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI'south 100 Years...100 Picture show Quotes Nominees" (PDF) . Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's x Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July xvi, 2011. Retrieved Baronial 19, 2016.

Bibliography [edit]

- Boswell, John (February 15, 2009). Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century. University of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0-226-06714-viii.

- Brown, Gene (November ane, 1995). Moving-picture show time: a chronology of Hollywood and the moving-picture show industry from its beginnings to the present . Macmillan. ISBN978-0-02-860429-nine.

- Carr, Jay (January 2002). The A List: The National Gild of Movie Critics' 100 Essential Films . Da Capo Press. p. 48. ISBN978-0-306-81096-1.

- Cavell, Stanley (1981). Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage . Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-73906-2.

- Eliot, Marc (2004). Cary Grant: A Biography . New York: Harmony Books. ISBN978-0-307-20983-2.

- Hanson, Patricia King, ed. (1993). The American Film Found Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the Usa: Feature Films, 1931–1940. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-07908-iii.

- Laham, Nicholas (January 1, 2009). Currents of Comedy on the American Screen: How Moving-picture show and Television Deliver Different Laughs for Changing Times. McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-5383-2.

- Leaming, Barbara (1995). Katharine Hepburn . New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. ISBN978-0-87910-293-vii.

- Mast, Gerald (1988). Bringing Up Baby. Howard Hawks, director. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Printing. ISBN978-0-8135-1341-six.

- McCarthy, Todd (1997). Howard Hawks: The Grey Play tricks of Hollywood. New York: Grove Press. ISBN978-0-8021-3740-i.

- Russo, Vito (September xx, 1987). The Celluloid Cupboard: Homosexuality in the Movies . HarperCollins. ISBN978-0-06-096132-9.

Further reading

- Swaab, Peter (January 4, 2011). Bringing Up Baby. British Film Institute. ISBN978-ane-84457-070-half-dozen.

External links [edit]

- Bringing Upward Baby at IMDb

- Bringing Up Baby at AllMovie

- Bringing Up Babe at the TCM Moving-picture show Database

- Bringing Upward Babe at the American Film Institute Itemize

- Pauline Kael analysis

- Bringing Up Baby at moviediva

- Reprints of historic reviews, photo gallery at CaryGrant.cyberspace

- Bringing Up Babe on Theater of Romance: July 24, 1945

- Bringing Up Baby essay by Michael Schlesinger on the National Picture show Registry site. [ane]

- Bringing Upwards Baby: Bones, Balls, and Butterflies an essay past Sheila O'Malley at the Criterion Collection

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bringing_Up_Baby

Posted by: hibbittsnuthat.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Howard Hawks Peter John Ward Hawks"

Post a Comment